Difference between revisions of "Correlation Power Analysis"

(Added info on correlation + attacking a subkey) |

(Changed header levels) |

||

| (6 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

This page discusses some of the basics of these steps, describing what models are typically used in CPA attacks and how the Pearson correlation coefficient is calculated. | This page discusses some of the basics of these steps, describing what models are typically used in CPA attacks and how the Pearson correlation coefficient is calculated. | ||

| − | = Modeling Power Consumption = | + | == Modeling Power Consumption == |

Electronic computers (microcontrollers, FPGAs, etc) have two components to their power consumption. First, static power consumption is the power required to keep the device running. This static power depends on things like the number of transistors inside the device. Secondly, and more importantly, dynamic power consumption depends on the data moving around inside the device. Every time a bit is changed from a 0 to a 1 (or vice versa), some current is required to (dis)charge the data lines. The dynamic power is the part that we're interested in - it can tell us what's happening inside. | Electronic computers (microcontrollers, FPGAs, etc) have two components to their power consumption. First, static power consumption is the power required to keep the device running. This static power depends on things like the number of transistors inside the device. Secondly, and more importantly, dynamic power consumption depends on the data moving around inside the device. Every time a bit is changed from a 0 to a 1 (or vice versa), some current is required to (dis)charge the data lines. The dynamic power is the part that we're interested in - it can tell us what's happening inside. | ||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

| − | = Pearson's Correlation Coefficient = | + | == Pearson's Correlation Coefficient == |

Once we have a way to model our power consumption, we need a way to compare our power estimate to our measured traces. A helpful tool for finding this relationship is through Pearson's correlation coefficient, which is | Once we have a way to model our power consumption, we need a way to compare our power estimate to our measured traces. A helpful tool for finding this relationship is through Pearson's correlation coefficient, which is | ||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

* If <math>Y</math> is totally independent of <math>X</math>, it will be 0. | * If <math>Y</math> is totally independent of <math>X</math>, it will be 0. | ||

| − | + | These equations are referred to as the ''normalized cross-correlation''. There are typically used to pick out patterns in noisy signals. For example, in digital imaging, correlation can be used to find where an object is in a room. In our attack, we'll be looking for a our model (a pre-calculated pattern) in measured power traces (noisy signals). | |

| − | + | ||

| − | We'll also estimate the power consumption in each trace using our model. We'll say that there are <math>I</math> different subkeys that we want to try. Then, <math>h_{d, i}</math> will refer to our power estimate in trace <math>d</math>, assuming that the subkey is <math>i</math> (<math>1 \le d \le D, | + | == Attacking with Correlation == |

| + | After taking our measurements, we'll have <math>D</math> power traces <math>t</math>, and each of these traces will have <math>T</math> data points. Using subscript notation, <math>t_{d, j}</math> will refer to point <math>j</math> in trace <math>d</math> (<math>1 \le d \le D, 0 \le j < T</math>). | ||

| + | |||

| + | We'll also estimate the power consumption in each trace using our model. We'll say that there are <math>I</math> different subkeys that we want to try. Then, <math>h_{d, i}</math> will refer to our power estimate in trace <math>d</math>, assuming that the subkey is <math>i</math> (<math>1 \le d \le D, 0 \le i < I</math>). | ||

With this data, we can see how well our model and measurements match for each guess <math>i</math> and time <math>j</math>. We'll do this by finding how <math>t</math> and <math>h</math> correlate over the <math>D</math> traces. One way of calculating this is: | With this data, we can see how well our model and measurements match for each guess <math>i</math> and time <math>j</math>. We'll do this by finding how <math>t</math> and <math>h</math> correlate over the <math>D</math> traces. One way of calculating this is: | ||

| Line 69: | Line 71: | ||

Note that these two sums are equivalent. | Note that these two sums are equivalent. | ||

| − | = Picking a Subkey = | + | == Picking a Subkey == |

The last step is to use the values of <math>r_{i,j}</math> to decide which subkey matches our traces most closely. There are two steps to this: | The last step is to use the values of <math>r_{i,j}</math> to decide which subkey matches our traces most closely. There are two steps to this: | ||

* For each subkey <math>i</math>, find the highest value of <math>|r_{i,j}|</math>. This will discard the time information - we want to know how good our guess was, but we don't care where our guess matched the trace. | * For each subkey <math>i</math>, find the highest value of <math>|r_{i,j}|</math>. This will discard the time information - we want to know how good our guess was, but we don't care where our guess matched the trace. | ||

| Line 75: | Line 77: | ||

Note that we're only working with absolute values here because we don't care about the sign of the relationship. All we need to know is that a linear correlation exists. | Note that we're only working with absolute values here because we don't care about the sign of the relationship. All we need to know is that a linear correlation exists. | ||

| − | = Example: AES-128 = | + | == Example: AES-128 == |

| + | As an example, consider AES-128 encryption. The pseudo-code for this algorithm is: | ||

| + | <pre> | ||

| + | // AES-128 Cipher | ||

| + | // in: 128 bits (plaintext) | ||

| + | // out: 128 bits (ciphertext) | ||

| + | // w: 44 words, 32 bits each (expanded key) | ||

| + | state = in | ||

| − | + | AddRoundKey(state, w[0, Nb-1]) | |

| − | + | for round = 1 step 1 to Nr–1 | |

| + | SubBytes(state) // <-- Attack this point in round 1! | ||

| + | ShiftRows(state) | ||

| + | MixColumns(state) | ||

| + | AddRoundKey(state, w[round*Nb, (round+1)*Nb-1]) | ||

| + | end for | ||

| − | + | SubBytes(state) | |

| + | ShiftRows(state) | ||

| + | AddRoundKey(state, w[Nr*Nb, (Nr+1)*Nb-1]) | ||

| − | < | + | out = state |

| − | </ | + | </pre> |

| − | + | This might look pretty complex, but we only need to worry about one part of the algorithm. After the first <code>SubBytes()</code> step, the state is effectively | |

| + | <pre> | ||

| + | // State after AddRoundKey() and SubBytes() | ||

| + | state = sbox[in ^ key] | ||

| + | </pre> | ||

| + | where <code>sbox</code> is a lookup table used in AES. This is an effective point to attack. If we know that a byte of the plaintext is <math>p_d</math>, then our modeled power consumption will be | ||

| − | + | <math> | |

| + | h_{d, i} = \text{Hamming Weight}(\text{sbox}[p_d \oplus i]) | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| − | + | Then, we can proceed with the attack as described above. Since we are attacking one byte of the key at a time, we will have to try <math>I = 2^8</math> values for each subkey. Then, there are 16 bytes in the key, so our attack will take <math>16 \times 2^8 = 2^{12}</math> time. This is an enormous improvement over trying every possible key, which would take <math>2^{128}</math> time. | |

| − | + | [[Category:Theory]] | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | [[Category:TocTheory]] | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

Latest revision as of 05:29, 1 May 2018

Correlation Power Analysis (CPA) is an attack that allows us to find a secret encryption key that is stored on a victim device. There are 4 steps to a CPA attack:

- Write down a model for the victim's power consumption. This model will look at one specific point in the encryption algorithm. (ie: after step 2 of the encryption process, the intermediate result is

, so the power consumption is

, so the power consumption is  .)

.) - Get the victim to encrypt several different plaintexts. Record a trace of the victim's power consumption during each of these encryptions.

- Attack small parts (subkeys) of the secret key:

- Consider every possible option for the subkey. For each guess and each trace, use the known plaintext and the guessed subkey to calculate the power consumption according to our model.

- Calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient between the modeled and actual power consumption. Do this for every data point in the traces.

- Decide which subkey guess correlates best to the measured traces.

- Put together the best subkey guesses to obtain the full secret key.

This page discusses some of the basics of these steps, describing what models are typically used in CPA attacks and how the Pearson correlation coefficient is calculated.

Modeling Power Consumption

Electronic computers (microcontrollers, FPGAs, etc) have two components to their power consumption. First, static power consumption is the power required to keep the device running. This static power depends on things like the number of transistors inside the device. Secondly, and more importantly, dynamic power consumption depends on the data moving around inside the device. Every time a bit is changed from a 0 to a 1 (or vice versa), some current is required to (dis)charge the data lines. The dynamic power is the part that we're interested in - it can tell us what's happening inside.

One of the simplest models for power consumption is the Hamming Distance model. The Hamming Distance between two binary numbers is the number of different bits in the numbers. For example,

HammingDistance(00110000, 00100011) = 3

because there are 3 unequal bits in these two numbers. An easy way to calculate the Hamming Distance is

HammingDistance(x, y) = HammingWeight(x ^ y)

where ^ is the XOR operator, and the Hamming Weight is the number of 1s in a binary number. Using the example above,

HammingDistance(00110000, 00100011)

= HammingWeight(00010011)

= 3

because 00010011 has three bits set.

We can use the Hamming Distance model in our CPA attacks. If we can find a point in the encryption algorithm where the victim changes a variable from x to y, then we can estimate that the power consumption is proportional to Hamming Distance(x, y). Often, our model can even be a bit simpler: if we assume that the victim is replacing the value x = 0, then our power model is

l(y) = HammingWeight(y)

Pearson's Correlation Coefficient

Once we have a way to model our power consumption, we need a way to compare our power estimate to our measured traces. A helpful tool for finding this relationship is through Pearson's correlation coefficient, which is

![\rho_{X,Y}

= \frac{\text{cov}(X, Y)}{\sigma_X \sigma_Y}

= \frac{E[(X - \mu_X)(Y - \mu_Y)]}{\sqrt{E[(X - \mu_X)^2] E[(Y - \mu_Y)^2]}}](/images/math/6/b/d/x6bd4ce3d3dd6e48d0e20734a518847b0.png.pagespeed.ic.xTLckmfkK9.png)

This correlation coefficient will always be in the range [-1, 1]. It describes how closely the random variables  and

and  are related:

are related:

- If

always increases when

always increases when  increases, it will be 1;

increases, it will be 1; - If

always decreases when

always decreases when  increases, it will be -1;

increases, it will be -1; - If

is totally independent of

is totally independent of  , it will be 0.

, it will be 0.

These equations are referred to as the normalized cross-correlation. There are typically used to pick out patterns in noisy signals. For example, in digital imaging, correlation can be used to find where an object is in a room. In our attack, we'll be looking for a our model (a pre-calculated pattern) in measured power traces (noisy signals).

Attacking with Correlation

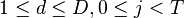

After taking our measurements, we'll have  power traces

power traces  , and each of these traces will have

, and each of these traces will have  data points. Using subscript notation,

data points. Using subscript notation,  will refer to point

will refer to point  in trace

in trace  (

( ).

).

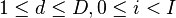

We'll also estimate the power consumption in each trace using our model. We'll say that there are  different subkeys that we want to try. Then,

different subkeys that we want to try. Then,  will refer to our power estimate in trace

will refer to our power estimate in trace  , assuming that the subkey is

, assuming that the subkey is  (

( ).

).

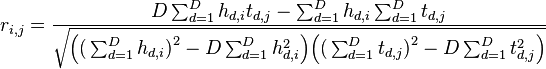

With this data, we can see how well our model and measurements match for each guess  and time

and time  . We'll do this by finding how

. We'll do this by finding how  and

and  correlate over the

correlate over the  traces. One way of calculating this is:

traces. One way of calculating this is:

![r_{i,j}

= \frac{{\sum\nolimits_{d = 1}^D {\left[ {\left( {{h_{d,i}} - \overline {{h_i}} } \right)\left( {{t_{d,j}} - \overline {{t_j}} } \right)} \right]} }}{{\sqrt {\sum\nolimits_{d = 1}^D {{{\left( {{h_{d,i}} - \overline {{h_i}} } \right)}^2}} \sum\nolimits_{d = 1}^D {{{\left( {{t_{d,j}} - \overline {{t_j}} } \right)}^2}} } }}](/images/math/d/9/1/xd916f67002b47caff1b8ea46751e4bf1.png.pagespeed.ic.CDstywW1XH.png)

There is an alternative form of the correlation equation that we can use for online calculations - it allows us to add one trace at a time without re-summing all of the past data. This form is:

Note that these two sums are equivalent.

Picking a Subkey

The last step is to use the values of  to decide which subkey matches our traces most closely. There are two steps to this:

to decide which subkey matches our traces most closely. There are two steps to this:

- For each subkey

, find the highest value of

, find the highest value of  . This will discard the time information - we want to know how good our guess was, but we don't care where our guess matched the trace.

. This will discard the time information - we want to know how good our guess was, but we don't care where our guess matched the trace. - Looking at the maximum values for each subkey, find the highest value of

. The location

. The location  of this maximum is our best guess: it correlated more closely with the traces than any other guess.

of this maximum is our best guess: it correlated more closely with the traces than any other guess.

Note that we're only working with absolute values here because we don't care about the sign of the relationship. All we need to know is that a linear correlation exists.

Example: AES-128

As an example, consider AES-128 encryption. The pseudo-code for this algorithm is:

// AES-128 Cipher

// in: 128 bits (plaintext)

// out: 128 bits (ciphertext)

// w: 44 words, 32 bits each (expanded key)

state = in

AddRoundKey(state, w[0, Nb-1])

for round = 1 step 1 to Nr–1

SubBytes(state) // <-- Attack this point in round 1!

ShiftRows(state)

MixColumns(state)

AddRoundKey(state, w[round*Nb, (round+1)*Nb-1])

end for

SubBytes(state)

ShiftRows(state)

AddRoundKey(state, w[Nr*Nb, (Nr+1)*Nb-1])

out = state

This might look pretty complex, but we only need to worry about one part of the algorithm. After the first SubBytes() step, the state is effectively

// State after AddRoundKey() and SubBytes() state = sbox[in ^ key]

where sbox is a lookup table used in AES. This is an effective point to attack. If we know that a byte of the plaintext is  , then our modeled power consumption will be

, then our modeled power consumption will be

![h_{d, i} = \text{Hamming Weight}(\text{sbox}[p_d \oplus i])](/images/math/2/e/a/x2eaa4c84c1b6677dcc72b0f3fa1cd48e.png.pagespeed.ic.AJv8IYVQG1.png)

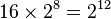

Then, we can proceed with the attack as described above. Since we are attacking one byte of the key at a time, we will have to try  values for each subkey. Then, there are 16 bytes in the key, so our attack will take

values for each subkey. Then, there are 16 bytes in the key, so our attack will take  time. This is an enormous improvement over trying every possible key, which would take

time. This is an enormous improvement over trying every possible key, which would take  time.

time.