| As of August 2020 the site you are on (wiki.newae.com) is deprecated, and content is now at rtfm.newae.com. |

Difference between revisions of "Tutorial A5-Bonus Breaking AES-256 Bootloader"

(Change header levels) |

|||

| Line 510: | Line 510: | ||

0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 3c | 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 3c | ||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Links == | ||

{{Template:Tutorials}} | {{Template:Tutorials}} | ||

[[Category:Tutorials]] | [[Category:Tutorials]] | ||

Revision as of 10:50, 1 May 2018

This tutorial is an add-on to Tutorial A5 Breaking AES-256 Bootloader. It continues working on the same firmware, showing how to obtain the hidden IV and signature in the bootloader. It is not possible to do this bonus tutorial without first completing the regular tutorial, so please finish Tutorial A5 first.

Contents

Exploring the Bootloader

In this tutorial, we have the luxury of seeing the source code of the bootloader. This is generally not something we would have access to in the real world, so we'll try not to use it to cheat. (Peeking at supersecret.h counts as cheating.) Instead, we'll use the source to help us identify important parts of the power traces.

Bootloader Source Code

Inside the bootloader's main loop, it does three tasks that we're interested in:

- it decrypts the incoming ciphertext;

- it applies the IV to the decryption's result; and

- it checks for the signature in the resulting plaintext.

This snippet from bootloader.c shows all three of these tasks:

// Continue with decryption

trigger_high();

aes256_decrypt_ecb(&ctx, tmp32);

trigger_low();

// Apply IV (first 16 bytes)

for (i = 0; i < 16; i++){

tmp32[i] ^= iv[i];

}

//Save IV for next time from original ciphertext

for (i = 0; i < 16; i++){

iv[i] = tmp32[i+16];

}

// Tell the user that the CRC check was okay

putch(COMM_OK);

putch(COMM_OK);

//Check the signature

if ((tmp32[0] == SIGNATURE1) &&

(tmp32[1] == SIGNATURE2) &&

(tmp32[2] == SIGNATURE3) &&

(tmp32[3] == SIGNATURE4)){

// Delay to emulate a write to flash memory

_delay_ms(1);

}

This gives us a pretty good idea of how the microcontroller is going to do its job. However, we can go one step further and find the exact assembly code that the target will execute. If you have Atmel Studio and its toolchain on your computer, you can get the assembly file from the command line with

avr-objdump -m avr -D bootloader.hex > disassembly.txt

This will convert the hex file into assembly code, making it more human-readable. The important part of this assembly code is:

344: d3 01 movw r26, r6 346: 93 01 movw r18, r6 348: f6 01 movw r30, r12 34a: 80 81 ld r24, Z 34c: f9 01 movw r30, r18 34e: 91 91 ld r25, Z+ 350: 9f 01 movw r18, r30 352: 89 27 eor r24, r25 354: f6 01 movw r30, r12 356: 81 93 st Z+, r24 358: 6f 01 movw r12, r30 35a: ee 15 cp r30, r14 35c: ff 05 cpc r31, r15 35e: a1 f7 brne .-24 ; 0x348 360: fe 01 movw r30, r28 362: b1 96 adiw r30, 0x21 ; 33 364: 81 91 ld r24, Z+ 366: 8d 93 st X+, r24 368: e4 15 cp r30, r4 36a: f5 05 cpc r31, r5 36c: d9 f7 brne .-10 ; 0x364 36e: 84 ea ldi r24, 0xA4 ; 164 370: 0e 94 16 02 call 0x42c ; 0x42c 374: 84 ea ldi r24, 0xA4 ; 164 376: 0e 94 16 02 call 0x42c ; 0x42c 37a: 89 89 ldd r24, Y+17 ; 0x11 37c: 88 23 and r24, r24 37e: 09 f0 breq .+2 ; 0x382 380: 98 cf rjmp .-208 ; 0x2b2 382: 8a 89 ldd r24, Y+18 ; 0x12 384: 8b 3e cpi r24, 0xEB ; 235 386: 09 f0 breq .+2 ; 0x38a 388: 94 cf rjmp .-216 ; 0x2b2 38a: 8b 89 ldd r24, Y+19 ; 0x13 38c: 82 30 cpi r24, 0x02 ; 2 38e: 09 f0 breq .+2 ; 0x392 390: 90 cf rjmp .-224 ; 0x2b2 392: 8c 89 ldd r24, Y+20 ; 0x14 394: 8d 31 cpi r24, 0x1D ; 29 396: 09 f0 breq .+2 ; 0x39a 398: 8c cf rjmp .-232 ; 0x2b2 39a: 83 e3 ldi r24, 0x33 ; 51 39c: 97 e0 ldi r25, 0x07 ; 7 39e: 01 97 sbiw r24, 0x01 ; 1 3a0: f1 f7 brne .-4 ; 0x39e 3a2: 87 cf rjmp .-242 ; 0x2b2

We'll use both of the source files throughout the tutorial.

Power Traces

After the bootloader is finished the decryption process, it executes a couple of distinct pieces of code:

- To apply the IV, it uses an XOR operation;

- To store the new IV, it copies the previous ciphertext into the IV array;

- It sends two bytes on the serial port;

- It checks the bytes of the signature one by one.

We should be able to recognize these four parts of the code in the power traces. Let's modify our capture routine to find them.

Re-run the capture script and change a few settings:

- We'd like to skip over all of the decryption process. The source code around this point is:

trigger_high(); aes256_decrypt_ecb(&ctx, tmp32); /* encrypting the data block */ trigger_low();

so we can skip straight over the AES-256 function by triggering on a falling edge instead of a rising edge. Change this in the scope settings.

- We don't need as many samples now. Change the number of samples to 3000.

- If we decrypt multiple ciphertexts in a row, only the first one will use the secret IV - all of the others will use the previous ciphertext instead. To avoid this, we'll have to automatically reset the board.

- In the General Settings tab, change the Auxiliary Module to Reset AVR/XMEGA via CW-Lite.

- In the Aux Settings tab, change both delays to around 100 ms.

- Capture one trace and make sure that everything works.

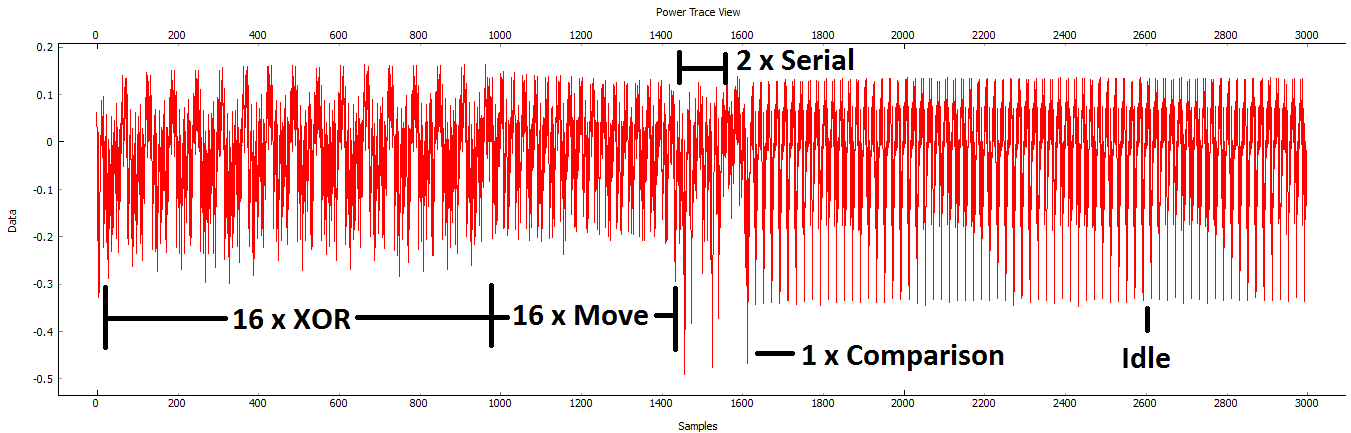

If everything worked out, you should be able to see all of the code's features:

With all of these things clearly visible, we have a pretty good idea of how to attack the IV and the signature. We should be able to look at each of the XOR spikes to find each of the IV bytes - each byte is processed on its own. Then, the signature check uses a short-circuiting comparison: as soon as it finds a byte in error, it stops checking the remaining bytes. This type of check is susceptible to a timing attack.

Let's grab a lot of traces so that we don't have to come back later. Save the project somewhere memorable, set up the capture routine to record 1000 traces, hit Capture Many, and grab a coffee.

Attacking the IV

We need to find the IV before we can look at the signature, so the first half of the attack will look at the IV bytes.

Attack Theory

The bootloader applies the IV to the AES decryption result by calculating

where DR is the decrypted ciphertext, IV is the secret vector, and PT is the plaintext that the bootloader will use later. We only have access to one of these: since we know the AES-256 key, we can calculate DR.

Specifically, the assembly code to calculate the plaintext is the loop

344: d3 01 movw r26, r6 346: 93 01 movw r18, r6 348: f6 01 movw r30, r12 34a: 80 81 ld r24, Z 34c: f9 01 movw r30, r18 34e: 91 91 ld r25, Z+ 350: 9f 01 movw r18, r30 352: 89 27 eor r24, r25 354: f6 01 movw r30, r12 356: 81 93 st Z+, r24 358: 6f 01 movw r12, r30 35a: ee 15 cp r30, r14 35c: ff 05 cpc r31, r15 35e: a1 f7 brne .-24 ; 0x348

This code includes two ld instructions, one eor, and one st: the DR and IV are loaded and XORed to get PT, which is then stored back where DR was. All of these instructions should be visible in the power traces.

This is enough information for us to attack a single bit of the IV. Suppose we only wanted to get the first bit (number 0) of the IV. We could do the following:

- Split all of the traces into two groups: those with DR[0] = 0, and those with DR[0] = 1.

- Calculate the average trace for both groups.

- Find the difference between the two averages. It should include a noticeable spike during the first iteration of the loop.

- Look at the direction of the spike to decide if the IV bit is 0 (

PT[0] = DR[0]) or if the IV bit is 1 (PT[0] = ~DR[0]).

This is effectively a DPA attack on a single bit of the IV. We can repeat this attack 128 times to recover the entire IV.

A 1-Bit Attack

Unfortunately, we can't use the ChipWhisperer Analyzer to attack this XOR function. Instead, we'll write our own Python code. One thing that we don't need to do is write our own AES-256 implementation: there's some perfectly fine code in the PyCrypto library. Install PyCrypto and make sure you can use its functions:

python Python 2.7.10 (default, May 23 2015, 09:40:32) [MSC v.1500 32 bit (Intel)] on win32 Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information. >>> from Crypto.Cipher import AES >>> AES <module 'Crypto.Cipher.AES' from 'C:\WinPython-32bit-2.7.10.3\python-2.7.10\lib\site-packages\Crypto\Cipher\AES.pyc'>

Next, open a new Python script wherever you like and load your data that you recorded earlier. You might want to rename the files to make them easier to work with. It'll also be helpful to know how many traces we have and how long they are:

# Load data import numpy as np traces = np.load(r'traces\traces.npy') textin = np.load(r'traces\textin.npy') numTraces = len(traces) traceLen = len(traces[0]) print numTraces print traceLen

It's also a good idea to plot some traces and make sure they look okay:

# Plot some traces

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

for i in range(10):

plt.plot(traces[i])

plt.show()

Since we know the AES-256 key, we can decrypt all of this data and store it in a list of decryption results:

# Decrypt ciphertext with the key that we now know

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

knownkey = [0x94, 0x28, 0x5D, 0x4D, 0x6D, 0xCF, 0xEC, 0x08, 0xD8, 0xAC, 0xDD, 0xF6, 0xBE, 0x25, 0xA4, 0x99,

0xC4, 0xD9, 0xD0, 0x1E, 0xC3, 0x40, 0x7E, 0xD7, 0xD5, 0x28, 0xD4, 0x09, 0xE9, 0xF0, 0x88, 0xA1]

knownkey = str(bytearray(knownkey))

dr = []

aes = AES.new(knownkey, AES.MODE_ECB)

for i in range(numTraces):

ct = str(bytearray(textin[i]))

pt = aes.decrypt(ct)

d = [bytearray(pt)[i] for i in range(16)]

dr.append(d)

print dr

That's a lot of data to print! Now, let's split the traces into two groups by comparing bit 0 of the DR:

# Split traces into 2 groups

groupedTraces = [[] for _ in range(2)]

for i in range(numTraces):

bit0 = dr[i][0] & 0x01

groupedTraces[bit0].append(traces[i])

print len(groupedTraces[0])

If you have 1000 traces, you should expect this to print a number around 500 - roughly half of the traces should fit into each group. Now, NumPy's average function lets us easily calculate the average at each point:

# Find averages and differences

means = []

for i in range(2):

means.append(np.average(groupedTraces[i], axis=0))

diff = means[1] - means[0]

Finally, we can plot this difference to see if we can spot the IV:

plt.plot(diff) plt.grid() plt.show()

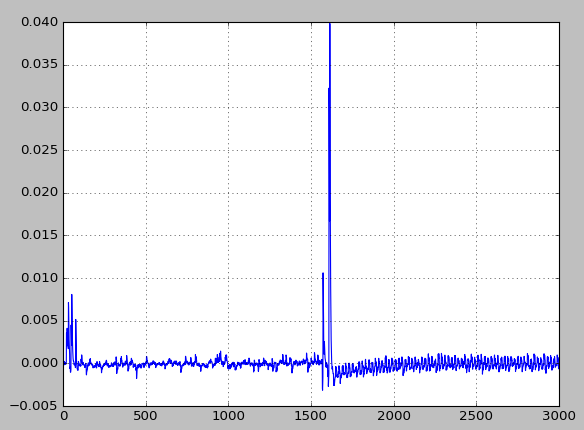

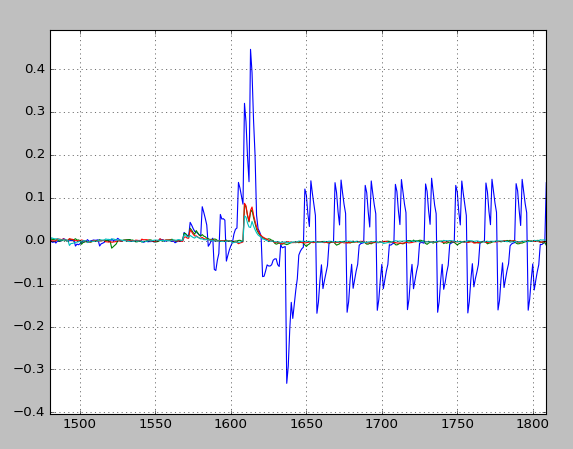

This makes a plot with some pretty obvious spikes:

However, one of these spikes is meaningless to us. The spike around sample 1600 is caused by the signature check, which we aren't attacking yet. You can get a better feel for this by plotting an overlay of the power trace itself:

plt.hold(True) plt.plot(traces[0], 'r') plt.plot(diff, 'b') plt.grid() plt.show()

You can notice the input data is often "pegging" to the 0.5 limit, indicating that spike may be caused by data overload! At any rate, it's clear the actual XOR is occurring where the group of 16 identical operations happens.

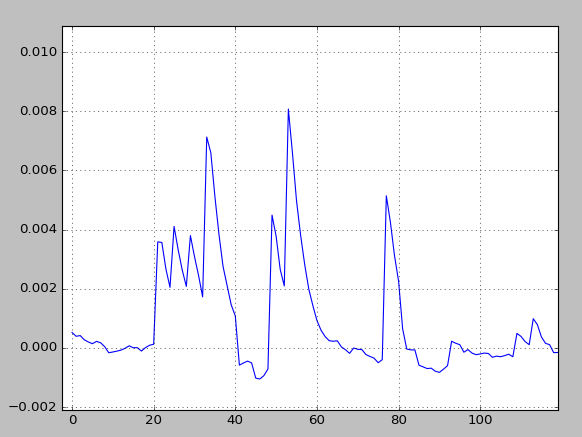

Let's ignore this large peak and zoom in on the smaller spikes at the start of the trace:

This is it! We've got a pretty clear signal telling us where the decryption result is used. You can make sure this isn't a coincidence by using the second byte instead:

These peaks are about 60 samples later (or 15 cycles, since we're using an ADC clock that's 4 times faster than the microcontroller). Also, most of these peaks are upside down! This is a pretty clear indicator that we can find the IV bits from these differential traces. The only thing that we can't tell is the polarity of these signals; there's no way to tell if right-side-up peaks indicate a bit that's set or cleared. However, that means we can narrow down the IV to two possibilities, which is a lot better than  .

.

The Other 127

The best way to attack the IV would be to repeat the 1-bit conceptual attack for each of the bits. Try to do this yourself! (Really!) If you're stuck, here are a few hints to get you going:

- One easy way of looping through the bits is by using two nested loops, like this:

for byte in range(16):

for bit in range(8):

# Attack bit number (byte*8 + bit)

- The sample that you'll want to look at will depend on which byte you're attacking. We had success when we used

location = 51 + byte*60, but your mileage will vary. - The bitshift operator and the bitwise-AND operator are useful for getting at a single bit:

# This will either result in a 0 or a 1 checkIfBitSet = (byteToCheck >> bit) & 0x01

If you're really, really stuck, there's a working attack in #Appendix A: IV Attack Script. You should find that the secret IV is C1 25 68 DF E7 D3 19 DA 10 E2 41 71 33 B0 EB 3C.

Attacking the Signature

The last thing we can do with this bootloader is attack the signature. This final section will show how one byte of the signature could be recovered. If you want more of this kind of analysis, a more complete timing attack is shown in Tutorial B3-1 Timing Analysis with Power for Password Bypass.

Attack Theory

Recall from earlier that the signature check in C looks like:

if ((tmp32[0] == SIGNATURE1) &&

(tmp32[1] == SIGNATURE2) &&

(tmp32[2] == SIGNATURE3) &&

(tmp32[3] == SIGNATURE4)){

or, in assembly,

37a: 89 89 ldd r24, Y+17 ; 0x11 37c: 88 23 and r24, r24 37e: 09 f0 breq .+2 ; 0x382 380: 98 cf rjmp .-208 ; 0x2b2 382: 8a 89 ldd r24, Y+18 ; 0x12 384: 8b 3e cpi r24, 0xEB ; 235 386: 09 f0 breq .+2 ; 0x38a 388: 94 cf rjmp .-216 ; 0x2b2 38a: 8b 89 ldd r24, Y+19 ; 0x13 38c: 82 30 cpi r24, 0x02 ; 2 38e: 09 f0 breq .+2 ; 0x392 390: 90 cf rjmp .-224 ; 0x2b2 392: 8c 89 ldd r24, Y+20 ; 0x14 394: 8d 31 cpi r24, 0x1D ; 29 396: 09 f0 breq .+2 ; 0x39a 398: 8c cf rjmp .-232 ; 0x2b2

In C, boolean expressions support short-circuiting. When checking multiple conditions, the program will stop evaluating these booleans as soon as it can tell what the final value will be. In this case, unless all four of the equality checks are true, the result will be false. Thus, as soon as the program finds a single false condition, it's done.

The assembly code confirms this short-circuiting operation. Each of the four assembly blocks include a comparison (and or cpi), a branch if equal (brqe), and a relative jump (rjmp). All four of the relative jumps return the program to the same location (the start of the while(1) loop), and all four of the branches try to avoid these relative jumps. If any of the comparisons are false, the relative jumps will return the program back to the start of the loop. All four branches must succeed to get into the body of the if block.

The short-circuiting conditions are perfect for us. We can use our power traces to watch how long it takes for the signature check to fail. If the check takes longer than usual, then we know that the first byte of our signature was right.

Finding a Single Byte

Okay, we know that our power trace will look a lot different for one of our choices of signatures. Let's figure out which one. We'll start by finding the average over all of our 1000 traces:

# Find the average over all of the traces mean = np.average(traces, axis=0)

Then, we'll split our traces into 256 different groups (one for each plaintext). Since we know the IV, we can now use it to recover the actual plaintext that the bootloader checks:

# Split the traces into groups

groupedTraces = [[] for _ in range(256)]

for i in range(numTraces):

group = dr[i][0] ^ 0xC1

groupedTraces[group].append(traces[i])

Next, we can find the mean for each group and see how much they differ from the overall mean:

# Find the mean for each group

means = np.zeros([256, traceLen])

for i in range(256):

if len(groupedTraces[i]) > 0:

means[i] = np.average(groupedTraces[i], axis=0)

plt.plot(means[0] - mean)

plt.plot(means[1] - mean)

plt.plot(means[2] - mean)

plt.plot(means[3] - mean)

plt.grid()

plt.show()

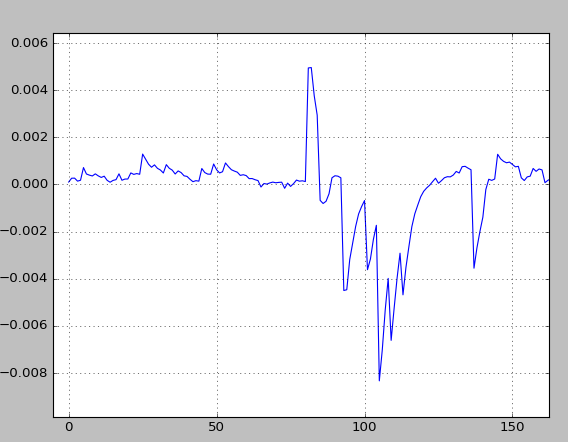

The plot that comes out of this should look a bit like:

Wow - looks like we found it! However, let's clean this up with some statistics. We can use the correlation coefficient to see which bytes are the furthest away from the average:

corr = []

for i in range(256):

corr.append(np.corrcoef(mean[1500:1700], means[i][1500:1700])[0, 1])

print np.sort(corr)

print np.argsort(corr)

This should print something that looks like:

[ 0.67663819 0.9834704 0.98855246 0.98942869 0.98994226 0.99019698 0.99082752 0.99159262 0.99166859 0.99169598 0.99216366 0.99229359 0.99239152 0.99240231 0.99246389 0.99254908 0.99258285 0.9926239 0.99280577 0.99302107 0.99339631 0.99394492 0.99396965 0.99403114 0.99408231 0.99410649 0.99424916 0.99460312 0.99464971 0.99468856 0.99483947 0.99512576 0.99553707 0.99570373 0.99572752 0.99577311 0.99582226 0.99587666 0.99590395 0.99623462 0.99630861 0.99639056 0.99644546 0.99646228 0.99653183 0.99661089 0.9966309 0.99665822 0.9966832 0.99670105 0.99673815 0.99679397 0.99690167 0.99692316 0.9969269 0.99694459 0.99703105 0.99704228 0.99705158 0.99708642 0.99709179 0.9971024 0.99710707 0.99711091 0.99711536 0.99715928 0.99720665 0.99721363 0.99721902 0.99722437 0.99722547 0.99723478 0.99724198 0.997244 0.99724712 0.99728416 0.99728622 0.99729196 0.99734564 0.99737952 0.99739401 0.99742793 0.99745246 0.99747648 0.99750044 0.9975651 0.99760837 0.99762965 0.99763106 0.99763222 0.99765327 0.9976662 0.9976953 0.99769761 0.99771007 0.99773553 0.99775314 0.99777414 0.99782335 0.99785114 0.99786062 0.99787688 0.99788584 0.99788938 0.9978924 0.99793722 0.99797874 0.99798273 0.9980249 0.99807047 0.99807947 0.99810194 0.99813208 0.9982722 0.99838807 0.99843216 0.99856034 0.99856295 0.99863064 0.9987529 0.99878124 0.99882028 0.99884917 0.99890103 0.99890116 0.99890879 0.99891135 0.99891317 0.99893291 0.99893508 0.99894488 0.99894848 0.99897892 0.99898304 0.9989834 0.99898804 0.99901833 0.99905207 0.99905642 0.99905798 0.99908281 0.99910538 0.99911272 0.99911782 0.99912193 0.99912223 0.9991229 0.99914415 0.99914732 0.99916885 0.99917188 0.99917941 0.99918178 0.99919009 0.99921141 0.99923463 0.99924823 0.99924986 0.99925438 0.99925524 0.99926407 0.99927205 0.99927364 0.99928305 0.99928533 0.99929447 0.99929925 0.99930205 0.99930243 0.99930623 0.99931579 0.99932861 0.99933414 0.99933806 0.99933992 0.99934213 0.99935681 0.99935721 0.9993594 0.9993601 0.99936267 0.99936373 0.99936482 0.99937458 0.99937665 0.99937706 0.99938049 0.99938241 0.99938251 0.999391 0.99940622 0.9994087 0.99940929 0.9994159 0.99941886 0.99942033 0.99942274 0.99942601 0.9994279 0.99943674 0.99943796 0.99944123 0.99944152 0.99944193 0.99944859 0.9994499 0.99945661 0.9994776 0.99948316 0.99949018 0.9994928 0.99949457 0.99949475 0.99949542 0.99949547 0.99949835 0.99950941 0.99951938 0.99951941 0.99953141 0.9995379 0.99954004 0.99954337 0.99954548 0.99955606 0.9995565 0.99956179 0.99956494 0.99956494 0.99956716 0.99957014 0.99957477 0.99957663 0.99958413 0.99958574 0.99958651 0.99958795 0.99958879 0.99959042 0.99959141 0.99959237 0.99959677 0.99961313 0.99962923 0.99963177 0.9996504 0.99968832 0.99969333 0.99969583 0.99969834 0.99970998 0.99972495 0.99972646 nan nan nan] [ 0 32 128 255 160 223 8 16 48 96 40 1 95 215 2 33 34 64 4 36 127 207 239 254 253 247 222 251 159 191 221 219 80 129 136 176 168 192 144 56 224 162 130 119 87 72 132 24 126 9 17 111 123 18 112 68 63 125 79 3 66 93 94 49 42 161 237 206 31 35 104 20 98 245 37 238 10 65 52 50 246 231 243 44 41 183 5 6 214 97 190 12 250 220 91 175 199 252 205 249 189 151 235 143 218 157 158 213 203 38 100 211 187 217 155 55 200 226 11 107 138 120 152 23 103 137 81 145 25 30 118 109 110 60 7 184 202 146 117 21 225 177 131 208 77 148 78 193 71 85 140 196 133 47 185 115 15 86 233 169 61 172 194 232 122 186 62 92 102 75 124 212 116 29 150 180 156 57 230 121 90 182 240 167 76 170 165 88 43 229 166 46 147 27 188 163 149 19 198 51 210 53 73 83 142 135 59 114 22 197 241 45 236 227 89 174 82 67 13 244 14 181 228 69 195 58 39 26 242 173 113 74 179 141 106 99 234 105 216 28 139 153 209 201 204 248 54 108 84 171 101 70 154 164 134 178]

This output tells us two things:

- The first list says that almost every trace looks very similar to the overall mean (98% correlated or higher). However, there's one trace that is totally different, with 68% correlation. This is probably our correct guess.

- The second list gives the signature guess that matches each of the above correlations. The first number in the list is 0x00, which is the correct signature!

Note that three numbers in this output show a correlation of nan because none of the captured traces had any data on them. However, this doesn't matter to us - we found our byte.

To finish this attack, you could force the capture software to send more specific text. To find the next byte of the signature, you'd want to fix byte 0 at 0x00 and make byte 1 random. Then, the plaintext should be XORed with the known IV and encrypted with the known AES-256 key. This is left as an exercise for the reader.

Appendix A: IV Attack Script

This is the author's script to automatically attack the secret IV. If you've completed #A 1-Bit Attack, you can paste this snippet immediately after it:

# Attack!

for byte in range(16):

location = 51 + byte * 60

iv = 0

for bit in range(8):

# Check if the decrypted bits are 0 or 1

pt_bits = [((dr[i][byte] >> (7 - bit)) & 0x01) for i in range(numTraces)]

# Split the traces into two groups

groupedPoints = [[] for _ in range(2)]

for i in range(numTraces):

groupedPoints[pt_bits[i]].append(traces[i][location])

# Get the means for each bit and subtract them

means = []

for i in range(2):

means.append(np.average(groupedPoints[i]))

diff = means[1] - means[0]

# Look in point of interest location

iv_bit = 1 if diff > 0 else 0

iv = (iv << 1) | iv_bit

print iv_bit,

print "%02x" % iv

The output from this script is:

1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 c1 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 25 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 68 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 df 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 e7 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 d3 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 19 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 da 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 10 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 e2 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 41 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 71 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 33 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 b0 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 eb 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 3c