| As of August 2020 the site you are on (wiki.newae.com) is deprecated, and content is now at rtfm.newae.com. |

Difference between revisions of "Attacking TEA with CPA"

(→Attacking the Key) |

(Add link to xbox attack) |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

} | } | ||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

| − | If you're used to looking at the AES algorithm, this one probably looks extremely simple. However, it is surprisingly secure. As of 2016, very few attacks on TEA are known - the best cryptanalysis results require <math>2^{121.5}</math> guesses against a shortened version of the algorithm! The only real weakness is that every key has three other equivalent keys - that is, there are four different keys that all give the exact same encrypted output. This is not a showstopper because <math>2^{126}</math> keys is still too many to brute-force. | + | If you're used to looking at the AES algorithm, this one probably looks extremely simple. However, it is surprisingly secure. As of 2016, very few attacks on TEA are known - the best cryptanalysis results require <math>2^{121.5}</math> guesses against a shortened version of the algorithm! The only real weakness is that every key has three other equivalent keys - that is, there are four different keys that all give the exact same encrypted output. This is not a showstopper because <math>2^{126}</math> keys is still too many to brute-force (it does mean the algorithm is a poor choice for certain applications such as hashes, something the [https://web.archive.org/web/20090416175601/http://www.xbox-linux.org/wiki/17_Mistakes_Microsoft_Made_in_the_Xbox_Security_System#The_TEA_Hash XBox security missed]). |

In order to complete a CPA attack, we need to find some sensitive points of the algorithm. Breaking up the first round of the one-liner | In order to complete a CPA attack, we need to find some sensitive points of the algorithm. Breaking up the first round of the one-liner | ||

Revision as of 08:09, 5 July 2016

Contents

TEA Encryption

TEA (Tiny Encryption Algorithm) is a simple encryption algorithm that is meant to be simple enough to memorize. It uses a 128 bit key to encrypt 64 bits of plaintext with the following C code:

void tea_encrypt(uint32_t* v, uint32_t* k)

{

uint32_t sum=0, i;

uint32_t delta= 0x9e3779b9;

for (i=0; i < 32; i++) {

sum += delta;

v[0] += ((v[1]<<4) + k[0]) ^ (v[1] + sum) ^ ((v[1]>>5) + k[1]);

v[1] += ((v[0]<<4) + k[2]) ^ (v[0] + sum) ^ ((v[0]>>5) + k[3]);

}

}

If you're used to looking at the AES algorithm, this one probably looks extremely simple. However, it is surprisingly secure. As of 2016, very few attacks on TEA are known - the best cryptanalysis results require  guesses against a shortened version of the algorithm! The only real weakness is that every key has three other equivalent keys - that is, there are four different keys that all give the exact same encrypted output. This is not a showstopper because

guesses against a shortened version of the algorithm! The only real weakness is that every key has three other equivalent keys - that is, there are four different keys that all give the exact same encrypted output. This is not a showstopper because  keys is still too many to brute-force (it does mean the algorithm is a poor choice for certain applications such as hashes, something the XBox security missed).

keys is still too many to brute-force (it does mean the algorithm is a poor choice for certain applications such as hashes, something the XBox security missed).

In order to complete a CPA attack, we need to find some sensitive points of the algorithm. Breaking up the first round of the one-liner

v[0] += ((v[1]<<4) + k[0]) ^ (v[1] + sum) ^ ((v[1]>>5) + k[1]);

gives

uint32_t a = (v[1] << 4) + k[0]; // Attack point 1 uint32_t b = v[1] + 0x9e3779b9; // uint32_t c = (v[1] >> 5) + k[1]; // Attack point 2 v[0] += (a ^ b ^ c); // Attack point 3

The three attack points here are good spots to attack because they are non-linear: addition can cause a single changed bit to carry through to several bits of the result. However, all three of these points have limitations.

- This expression includes a left-shift of 4 bits, so we have no control over the bottom 4 bits. This means we cannot use CPA to recover all 32 bits of

k[0]- we can only get 28 of them. - Similarly, this expression includes a right-shift of 5 bits, so we can only get at the bottom 27 bits.

- The last XOR combines the first two results, which use both words of the key (

k[0]andk[1]). This means that we can only use it if we already know some of the bits in one of these keys (ie: we can only find the first byte ofk[0]if we know the first byte ofk[1]).

However, this is enough information to recover both of these words. Once we know these 64 bits, the second half of the key can be recovered in exactly the same way.

Firmware

The AES SimpleSerial target was adapted to use TEA encryption instead of AES. This new target uses the exact same commands as the original SimpleSerial target:

-

kKEYloads KEY as the 128 bit encryption key -

pPLAINTEXTloads PLAINTEXT as the 64 bit plaintext and begins the encryption routine -

rRESPONSEis the reply from the target, where RESPONSE is the 64 bit ciphertext

This firmware is available in chipwhisperer/hardware/victims/firmware/simpleserial-tea. It uses the same build process as the other targets - simply run make to produce the hex file.

Capture

The setup for this capture routine will be pretty straightforward because the firmware is so close to the SimpleSerial targets we've attacked before. Only a small number of modifications need to be made to adapt the capture script for TEA.

- First, run the AES SimpleSerial example script (

Project > Example Scripts > ChipWhisperer-Lite: AES SimpleSerial on XMEGA). This will connect to the hardware and prepare most of the settings. - Open the programmer (

Tools > CW-Lite XMEGA Programmer) and find the hex file that we made in the previous section. Flash this program onto the target. - Under Target Settings, change the Input Length and Output Length from 16 to 8 bytes to match the TEA code (64 bit plaintext and ciphertext).

- Under Scope Settings, change the trigger offset to 0 samples.

All of the other default settings are fine.

Before starting the full captures, open the Encryption Monitor (Tools > Encryption Status Monitor) and press Capture 1. Confirm that the Text In and Text Out are 8 bytes long, like we specified above. If you want to test a specific case, when the input and key are both all 0s, the output is 41 EA 3A 0A 94 BA A9 40.

For our analysis, we'll need two sets of data. The first should have random keys and plaintexts, and the second should have a fixed ("secret") key and random plaintexts. For this guide, I'll be using a fixed key of 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 0A 0B 0C 0D 0E 0F. Capture about 1000 traces for each set and put all of the data files in a convenient place.

Analysis

Searching for Leakage

Our first step is to look through the traces to see if there's any visible leakage. We can do this by sorting the traces into appropriate groups and comparing the averages of each group. This section will look a lot like Tutorial B6 Breaking AES (Manual CPA Attack), so you might want to make a copy of this script for a starting point.

First of all, find the random-key traces and load them with NumPy:

import numpy as np

traces = np.load('traces/traces.npy')

text = np.load('traces/textin.npy')

keys = np.load('traces/keylist.npy')

num_traces = len(traces)

Next, we'll make a list to split our traces into 9 groups (one for each Hamming weight):

grouped_traces = [[] for _ in range(9)]

Then, for each trace, we need to calculate one of the sensitive intermediate values and find the Hamming weight. There are a few steps to this; for each trace, we need to:

- Use the plaintext we loaded to build the

varray (32 bit words, instead of bytes) - Use the key to build the

karray (again, 32 bit words) - Calculate the intermediate values (watch out for overflow - you can keep things at 32 bits by ANDing your variables with

0xffffffff) - Find the Hamming weight of the intermediate values

- Put the trace into one of the 9 groups

Try this yourself! If you're stuck, here's my implementation:

for i in range(num_traces):

# Build the v array

v = [( text[i][0] << 24

| text[i][1] << 16

| text[i][2] << 8

| text[i][3]),

( text[i][4] << 24

| text[i][5] << 16

| text[i][6] << 8

| text[i][7])]

# Build the k array

k = [( keys[i][0] << 24

| keys[i][1] << 16

| keys[i][2] << 8

| keys[i][3]),

( keys[i][4] << 24

| keys[i][5] << 16

| keys[i][6] << 8

| keys[i][7])]

# Calculate the intermediate values

sum = 0x9e3779b9

mask = 0xffffffff

int1 = ((v[1] << 4) + k[0]) & mask

int2 = (v[1] + sum) & mask

int3 = ((v[1] >> 5) + k[1]) & mask

int = ((int1 ^ int2 ^ int3)) & mask

# Figure out which group this trace goes in

# Change this line to look for different attack points

group = bin((int1) & 0xFF).count('1')

grouped_traces[group].append(traces[i])

Once we have the traces in groups, we can find the mean of each group and plot everything:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Find means and plot

means = []

for i in range(9):

print i, len(grouped_traces[i])

means.append(np.average(grouped_traces[i], axis=0))

plt.plot(means[i])

plt.grid()

plt.show()

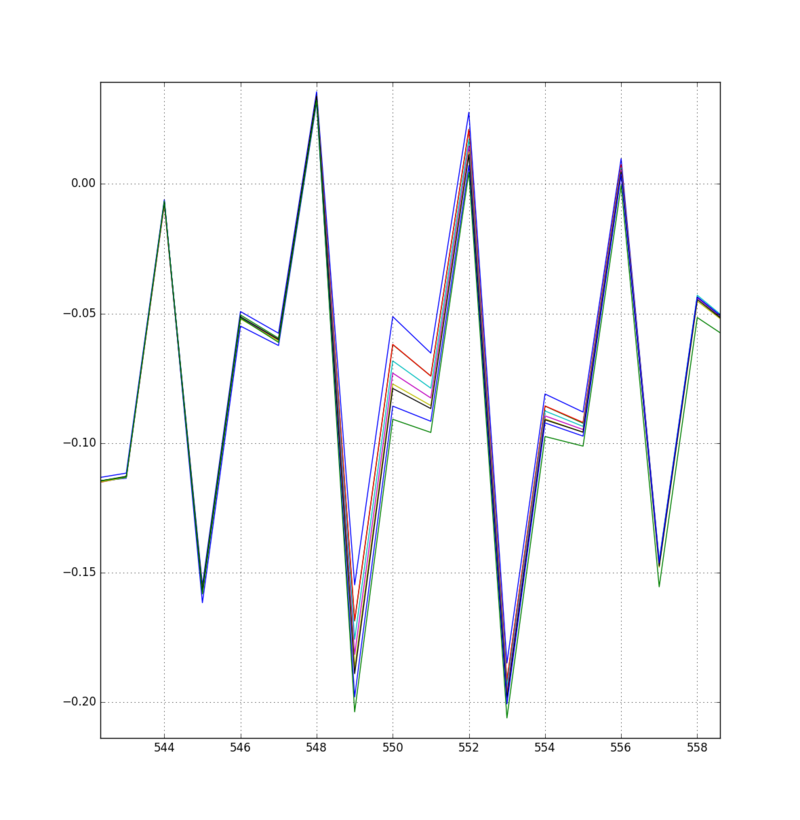

With some luck, you should be able to find a point where the averages are noticeably different. For example, this point varies quite a bit when the first attack point changes in Hamming weight:

If you need some help searching, you could also try plotting means[7] - means[1]. This plot will have large spikes whenever these two means are different, making it easier to find places to look. Do this for all three of our attack points and make sure that you can spot all of them.

Creating More Leakage

This is where things get tough. When I worked through these plots, I found pretty clear signals that showed me the Hamming weight of attack point 1 (int1) and 3 (v[0] + int). However, I couldn't find the second point anywhere. Since we need all three points to complete the attack, I took some drastic measures. If you're also stuck, keep reading.

One way to get more leakage out of the target is to turn off optimizations in the compiler. This will usually cause the CPU to perform more reads and writes to memory, which are not always necessary. These extra operations made it much easier to find the missing leakage. To turn off optimizations, go back to the firmware folder, open the Makefile in a text editor, and find the line

# Optimization level, can be [0, 1, 2, 3, s]. # 0 = turn off optimization. s = optimize for size. # (Note: 3 is not always the best optimization level. See avr-libc FAQ.) OPT = s

Change this s to 0 and re-make the firmware. Then, repeat the capture setup and record another 2000 traces. Re-run the analysis script and confirm that the leakage is clearly visible.

Attacking the Key

Since we know that our traces show us some leakage, we can complete our attack. We'll start a new script by writing functions to calculate our three attack point values:

def intermediate_1(v, k):

v1 = ( v[4] << 24

| v[5] << 16

| v[6] << 8

| v[7])

k0 = ( k[0] << 24

| k[1] << 16

| k[2] << 8

| k[3])

return ((v1 << 4) + k0) & 0xffffffff

def intermediate_2(v, k):

v1 = ( v[4] << 24

| v[5] << 16

| v[6] << 8

| v[7])

k1 = ( k[4] << 24

| k[5] << 16

| k[6] << 8

| k[7])

return ((v1 >> 5) + k1) & 0xffffffff

def intermediate_3(v, k):

v0 = ( v[0] << 24

| v[1] << 16

| v[2] << 8

| v[3])

v1 = ( v[4] << 24

| v[5] << 16

| v[6] << 8

| v[7])

k0 = ( k[0] << 24

| k[1] << 16

| k[2] << 8

| k[3])

k1 = ( k[4] << 24

| k[5] << 16

| k[6] << 8

| k[7])

int1 = ((v1 << 4) + k0) & 0xffffffff

int2 = (v1 + 0x9e3779b9) & 0xffffffff

int3 = ((v1 >> 5) + k1) & 0xffffffff

return v0 + (int1 ^ int2 ^ int3)

Then, we'll copy in the CPA attack script from Tutorial B6 and make some modifications. The full script for the TEA attack is:

traces = np.load('traces/O0_rand_traces.npy')

pt = np.load('traces/O0_rand_textin.npy')

knownkey = np.load('traces/O0_rand_keylist.npy')

#print knownkey

numtraces = np.shape(traces)[0]

numpoint = np.shape(traces)[1]

# Use less than the maximum traces by setting numtraces to something smaller

numtraces = 1000

bestguess = 0

cpaoutput = [0]*256

maxcpa = [0]*256

for kguess in range(0, 256):

print "Key = %02x: "%(kguess),

# Build our key guess

k = [0, 0, 0, kguess, 0, 0, 0, 0]

#Initialize arrays and variables to zero

sumnum = np.zeros(numpoint)

sumden1 = np.zeros(numpoint)

sumden2 = np.zeros(numpoint)

# Calculate hypothesis = Hamming weight of intermediate values

hyp = np.zeros(numtraces)

for tnum in range(0, numtraces):

int = (intermediate_1(pt[tnum], k) >> 0) & 0xff

hyp[tnum] = HW[int]

#Means of hypothesis and traces

meanh = np.mean(hyp, dtype=np.float64)

meant = np.mean(traces, axis=0, dtype=np.float64)

#For each trace, calculate correlation

for tnum in range(0, numtraces):

hdiff = (hyp[tnum] - meanh)

tdiff = traces[tnum,:] - meant

sumnum = sumnum + (hdiff*tdiff)

sumden1 = sumden1 + hdiff*hdiff

sumden2 = sumden2 + tdiff*tdiff

cpaoutput[kguess] = sumnum / np.sqrt( sumden1 * sumden2 )

maxcpa[kguess] = max(abs(cpaoutput[kguess]))

print maxcpa[kguess]

bestguess = np.argmax(maxcpa)

cparefs = np.argsort(maxcpa)[::-1]

print "Best Key Guess: %02x"%(bestguess)

print [hex(c) for c in cparefs]

There's one line of this script that we'll need to change a few times. In the key-guessing loop, we build the key by writing

k = [0, 0, 0, kguess, 0, 0, 0, 0]

and we calculate the intermediate value as

int = (intermediate_1(pt[tnum], k) >> 0) & 0xff

This means that we're only going to be modifying one byte of our guess - the other 7 bytes will remain unchanged - and we're only looking at the first byte of attack point 1. Once we're done attacking this byte, we can move our guess to a different byte and examine a different part of the intermediate value to continue the attack.

Run the script. You should see an output that looks like

Key = 00: 0.491256496954 Key = 01: 0.491256496954 Key = 02: 0.491256496954 Key = 03: 0.491256496954 Key = 04: 0.491256496954 Key = 05: 0.491256496954 Key = 06: 0.491256496954 Key = 07: 0.491256496954 Key = 08: 0.491256496954 Key = 09: 0.491256496954 Key = 0a: 0.491256496954 Key = 0b: 0.491256496954 Key = 0c: 0.491256496954 Key = 0d: 0.491256496954 Key = 0e: 0.491256496954 Key = 0f: 0.491256496954 Key = 10: 0.25438721963 Key = 11: 0.25438721963 Key = 12: 0.25438721963 Key = 13: 0.25438721963 Key = 14: 0.25438721963 Key = 15: 0.25438721963 Key = 16: 0.25438721963 Key = 17: 0.25438721963 Key = 18: 0.25438721963 Key = 19: 0.25438721963 Key = 1a: 0.25438721963 Key = 1b: 0.25438721963 Key = 1c: 0.25438721963 Key = 1d: 0.25438721963 Key = 1e: 0.25438721963 Key = 1f: 0.25438721963 ... <removed> Key = f0: 0.208801829135 Key = f1: 0.208801829135 Key = f2: 0.208801829135 Key = f3: 0.208801829135 Key = f4: 0.208801829135 Key = f5: 0.208801829135 Key = f6: 0.208801829135 Key = f7: 0.208801829135 Key = f8: 0.208801829135 Key = f9: 0.208801829135 Key = fa: 0.208801829135 Key = fb: 0.208801829135 Key = fc: 0.208801829135 Key = fd: 0.208801829135 Key = fe: 0.208801829135 Key = ff: 0.208801829135 Best Key Guess: 00 ['0x0', '0xb', '0x4', '0x5', '0x6', '0x7', '0x8', '0xa', '0x9', '0x3', '0xc', '0xd', ...

This tells us a few things. First of all, like we expected, we can't attack the bottom four bits of k[0] because the correlation coefficient isn't affected by these bits. Second, the most likely value of the top four bits is 0x0.

Change the attack script to

k = [0, 0, kguess, 0x00, 0, 0, 0, 0] ... int = (intermediate_1(pt[tnum], k) >> 8) & 0xff

and run it again. The correlation coefficients should be much different. My output shows Best Key Guess: 02, which is correct.

Continue this process:

- Repeat the same attack for the first two bytes of the key.

intermediate_1shifted by 16 and 24 bits should have no trouble with this. - To get the other half of the key, change the attack to

k = [0x00, 0x01, 0x02, 0x00, 0, 0, 0, kguess] ... int = (intermediate_2(pt[tnum], k) >> 0) & 0xff

- and attack all four bytes like before. Note that you will not recover the top 5 bits of

k[1]this way.

- To clean up the two incomplete bytes, switch to

intermediate_3and retry these two guesses.

If all goes well, you should be able to recover the entire key this way!

More Ideas

This guide has walked through a very basic CPA attack on TEA encryption. However, we could take this a lot further...

- This was a very "manual" attack: we had to guide our code through each of the single-byte attacks. It would be good to have a more automatic attack that combines all of the information from all three attack points, rather than picking and choosing bytes to attack.

- We had to use a lower optimization level so that we could see the power signature from the sensitive attack points. Can we avoid this? Maybe it's possible to use a different sampling method to find more leakage.

- A template attack might be a more powerful way to perform this attack. There are several points that we could create a template for, including the three points that we examined in this attack.