Tutorial B11 Breaking RSA

RSA Attack Theory

We won't go into what RSA is, see the RSA Wikipedia article for a quick background. What we really care about is the following pieces of sudocode from that article used in decrypting a message:

/**

* Decrypt

*

* @param {c} int / bigInt: the 'message' to be decoded (encoded with RSA.encrypt())

* @param {d} int / bigInt: d value returned from RSA.generate() aka private key

* @param {n} int / bigInt: n value returned from RSA.generate() aka public key (part I)

* @returns {bigInt} decrypted message

*/

RSA.decrypt = function(c, d, n){

return bigInt(c).modPow(d, n);

};

The most critical piece of information is that value d. It contains the private key, which if leaked would mean a compromise of the entire system. So let's assume we can monitor a target device while it decrypts any message (we don't even care what the message is). Our objective is to recover d.

Let's consider our actual target code, which will be the RSA implementation in avr-crypto-lib. This has been copied over to be part of the ChipWhisperer repository, and you can see the implementation rsa_basic.c of rsa_dec(). The function in question looks like this:

uint8_t rsa_dec(bigint_t* data, const rsa_privatekey_t* key){

if(key->n == 1){

bigint_expmod_u(data, data, &(key->components[0]), &key->modulus);

return 0;

}

if(key->n == 5){

if (rsa_dec_crt_mono(data, key)){

return 3;

}

return 0;

}

if(key->n<8 || (key->n-5)%3 != 0){

return 1;

}

//rsa_dec_crt_multi(data, key, (key->n-5)/3);

return 2;

}

We'll consider the case where key->n == 5, so we have the rsa_dec_crt_mono() to attack. You can see that function Line 53 of that same file. I've removed all the debug code in the following so you can better see the program flow:

uint8_t rsa_dec_crt_mono(bigint_t* data, const rsa_privatekey_t* key){

bigint_t m1, m2;

m1.wordv = malloc((key->components[0].length_B /* + 1 */) * sizeof(bigint_word_t));

m2.wordv = malloc((key->components[1].length_B /* + 1 */) * sizeof(bigint_word_t));

if(!m1.wordv || !m2.wordv){

//Out of memory error

free(m1.wordv);

free(m2.wordv);

return 1;

}

bigint_expmod_u(&m1, data, &(key->components[2]), &(key->components[0]));

bigint_expmod_u(&m2, data, &(key->components[3]), &(key->components[1]));

bigint_sub_s(&m1, &m1, &m2);

while(BIGINT_NEG_MASK & m1.info){

bigint_add_s(&m1, &m1, &(key->components[0]));

}

bigint_reduce(&m1, &(key->components[0]));

bigint_mul_u(data, &m1, &(key->components[4]));

bigint_reduce(data, &(key->components[0]));

bigint_mul_u(data, data, &(key->components[1]));

bigint_add_u(data, data, &m2);

free(m2.wordv);

free(m1.wordv);

return 0;

}

Note all the calls to bigint_expmod_u() with the private key material. If we could attack that function, all would be lost. These functions are elsewhere - it's in the bigint.c file at Line 812. Again we can see the source code here:

oid bigint_expmod_u(bigint_t* dest, const bigint_t* a, const bigint_t* exp, const bigint_t* r){

if(a->length_B==0 || r->length_B==0){

return;

}

bigint_t res, base;

bigint_word_t t, base_b[MAX(a->length_B,r->length_B)], res_b[r->length_B*2];

uint16_t i;

uint8_t j;

res.wordv = res_b;

base.wordv = base_b;

bigint_copy(&base, a);

bigint_reduce(&base, r);

res.wordv[0]=1;

res.length_B=1;

res.info = 0;

bigint_adjust(&res);

if(exp->length_B == 0){

bigint_copy(dest, &res);

return;

}

uint8_t flag = 0;

t=exp->wordv[exp->length_B - 1];

for(i=exp->length_B; i > 0; --i){

t = exp->wordv[i - 1];

for(j=BIGINT_WORD_SIZE; j > 0; --j){

if(!flag){

if(t & (1<<(BIGINT_WORD_SIZE-1))){

flag = 1;

}

}

if(flag){

bigint_square(&res, &res);

bigint_reduce(&res, r);

if(t & (1<<(BIGINT_WORD_SIZE-1))){

bigint_mul_u(&res, &res, &base);

bigint_reduce(&res, r);

}

}

t<<=1;

}

}

SET_POS(&res);

bigint_copy(dest, &res);

}

Within that file, the part is the loop at the end. This is actually going through and doing the required a**exp % r function. If you look closely into that loop, you can see there is a variable t, which is set to the value t = exp->wordv[i - 1];. After each run through the loop it is shifted left one. That t variable contains the private key, and the reason it is shifted left is the following piece of code is checking if the MSB is '0' or '1':

bigint_square(&res, &res);

bigint_reduce(&res, r);

if(t & (1<<(BIGINT_WORD_SIZE-1))){

bigint_mul_u(&res, &res, &base);

bigint_reduce(&res, r);

}

What does this mean? While there is data-dependent code execution! If we could determine the program flow, we could simply read the private key off one bit at a time. This will be our attack on RSA that we perform in this tutorial.

Hardware Setup

Building Example

Finding SPA Leakage

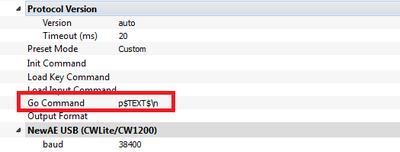

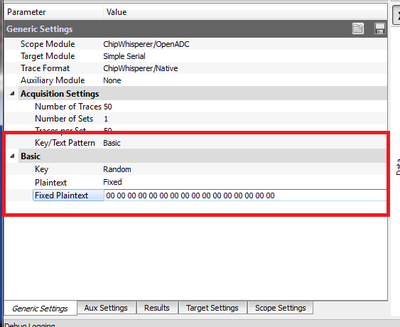

We'll now get into experimenting with the SPA leakage. To do so we'll use the "SPA Setup" script, then make a few modifications.

Run the SPA setup script.

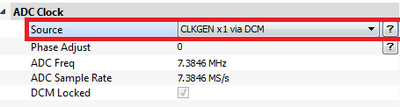

Change the CLKGEN to be CLKGEN x1 via DCM

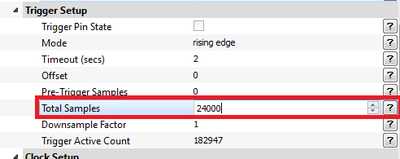

Change the length of the trigger to be 24000 samples:

If you are using Capture V3.5.2 or later you will have support for the length of the trigger output being high reported back to you. If you run capture-1 for example you'll see the trigger was high for XX cycles:

This is way too long! You won't be able to capture the entire trace in your 24000 length sample buffer. Instead we'll make the demo even shorter - in our case looking at the source code you can see there is a "flag" which is set high only AFTER the first 1 is received. Thus using a fixed plaintext, change the input plaintext to be

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

We'll only be able to change the LAST TWO bytes, everything else will be too slow. So change the input plaintext to

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 80 00

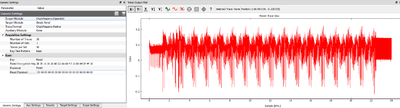

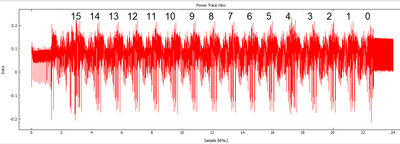

And you can see the power trace change drastically, as below:

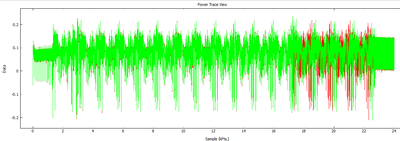

Finally, let's flip another bit. Change the input plaintext as follows, such that bit #4 in the final bit is set HIGH. We can plot the two power traces on top of each other, and you see that they are differing at a specific point in time:

Walking back from the right, you can see this almost directly matches bit numbering for those last two bytes:

Automating Attack

The final step is to automate this attack. There are a few ways to do this - we'll demonstrate a basic method, that you can extend to do a complete attack. In this example we're going to use a repeatable sequence, and look for the delay between this sequence. If we see a larger delay we know a square-multiply has occurred, otherwise it was only a square.

We'll simply define a "reference" sequence, and look for this sequence in the rest of the power trace. The following will be done in regular old Python, so start up your favorite Python editor to finish off the tutorial.