| As of August 2020 the site you are on (wiki.newae.com) is deprecated, and content is now at rtfm.newae.com. |

Difference between revisions of "Tutorial B8 Profiling Attacks (Manual Template Attack)"

(→Performing the Attack: Added section) |

(→Gotchas: Added section) |

||

| Line 324: | Line 324: | ||

= Gotchas = | = Gotchas = | ||

| − | + | One problem with template attacks is that they require a large amount of data to make good templates. Remember that every output of the AES substitution box is unique, so there is only one output with a Hamming weight of 0 and only one with a weight of 8. This means that, when using random inputs, there is only a 1/256 chance of a trace using a Hamming weight of 0 or 8. | |

| − | + | ||

| + | When only recording 1000 examples, it is completely possible to never see one of the weights, making it impossible to find the mean and variance. In fact, seeing a weight once is not enough - in order to calculate the variance, we need at least 2 traces, and this is hardly enough to build a good distribution. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Some template attacks involve building a separate distribution for every possible subkey. This makes the problem even worse - now, we have a 1/256 chance of finding every key, so it's quite probable to have insufficient data. The only solution is to record more traces. Practical template attacks may require tens of thousands of traces to get enough information. | ||

| + | |||

| + | If you ran into numerical problems while working through this tutorial, try recording another bigger data set. Instead of capturing 1000 template traces, try 5000 (on your coffee break), 10000 (on your lunch break), or 100000 (overnight). You'll probably find that the extra data makes the statistics work out better. | ||

{{Template:Tutorials}} | {{Template:Tutorials}} | ||

Revision as of 05:55, 26 May 2016

This tutorial is a more hands-on version of the previous tutorial. Rather than getting the ChipWhisperer Analyzer software to generate the points of interest and the template distributions, this tutorial will work directly with the recorded trace data in Python.

It is highly recommended that you read the theory page on Template Attacks before attempting this tutorial. There is some relatively complex processing involved, and it may be helpful to get a mathematical view on the steps before attempting to program them.

Additionally, this tutorial uses some terminology from previous tutorials, such as Hamming weight and substitution box. If you don't know what these are, Tutorial B6 Breaking AES (Manual CPA Attack) might be an easier starting point.

Contents

Scripting

All of the work in this tutorial will be done using Python scripts. All you need for this tutorial is a text editor and a command terminal that can run Python. In my example, I am editing a file called manualTemplate.py in a text editor and using the command

python manualTemplate.py

to execute the script. You can work with a full IDE if you prefer.

Capturing the Traces

As in the previous tutorial, this tutorial requires two sets of traces. The first set is a large number of traces (1000+) with random keys and plaintexts, assumed to come from your personal copy of the device. The second is a smaller number of traces (~50) with a fixed key and random plaintexts, assumed to come from the sensitive device that we're attacking. The goal of this tutorial is to recover the fixed key from the smaller set of traces.

The data collected from the previous tutorial will be fine for these steps. These examples will work with 2000 random-key traces and 50 fixed-key traces. If you don't have these datasets, follow the steps in Tutorial B7 Profiling Attacks (with HW Assumption) to record these traces.

Note that this tutorial will explain how to attack a single byte of the secret AES key. It would be easy to extend this to the full key by running the code 16 times. The smaller attack is used to make some of the code easier to grasp and debug.

Creating the Template

This section describes how to generate a template from the random-key traces. Our template will attempt to recognize the Hamming weight of the AES substitution box output. This choice of attack point limits our template - we will not be able to find the secret key in one attack trace - but it allows us to use a smaller amount of preprocessing. A more robust template attack (for instance, creating a template for each of the 256 possible key bytes) would require at least 10 times more data.

Loading the Traces

The traces recorded from the ChipWhisperer Capture program are saved as NumPy arrays. These files can be loaded using the np.load() function. We're interested in the traces, plaintext, and random keys used in our template captures, so we can load this data with the code:

import numpy as np tempTraces = np.load(r'C:\chipwhisperer\software\temp_attack\rand_key_data\traces\2016.05.24-12.53.15_traces.npy') tempPText = np.load(r'C:\chipwhisperer\software\temp_attack\rand_key_data\traces\2016.05.24-12.53.15_textin.npy') tempKey = np.load(r'C:\chipwhisperer\software\temp_attack\rand_key_data\traces\2016.05.24-12.53.15_keylist.npy')

(Of course, fill in your own filenames.)

We can check this data to make sure it looks okay. Some useful checks might be:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt print tempPText print len(tempPText) plt.plot(tempTraces[0]) plt.show()

Get in the habit of checking your data with some basic print statements or plots - it's a good sanity check to make sure that your arrays are the size they should be! If everything looks okay, comment out these checks and move on.

Sorting the Traces

With the data in-hand, our next task is to group the data according to our model. We're attacking an intermediate result in the AES algorithm where

intermediate = sbox[plaintext ^ key]

In our attack, we're going to try to look at a trace and decide what the Hamming weight of this intermediate result is. To set up the templates, we need to sort our template traces into 9 groups. The first group will be all of the traces that have an intermediate Hamming weight of 0. The next group has a Hamming weight of 1, etc..., and the last group has a Hamming weight of 8.

To find which group a trace belongs in, we can calculate the intermediate result from the plaintext and key. Some Python code to do this is:

sbox=(

0x63,0x7c,0x77,0x7b,0xf2,0x6b,0x6f,0xc5,0x30,0x01,0x67,0x2b,0xfe,0xd7,0xab,0x76,

0xca,0x82,0xc9,0x7d,0xfa,0x59,0x47,0xf0,0xad,0xd4,0xa2,0xaf,0x9c,0xa4,0x72,0xc0,

0xb7,0xfd,0x93,0x26,0x36,0x3f,0xf7,0xcc,0x34,0xa5,0xe5,0xf1,0x71,0xd8,0x31,0x15,

0x04,0xc7,0x23,0xc3,0x18,0x96,0x05,0x9a,0x07,0x12,0x80,0xe2,0xeb,0x27,0xb2,0x75,

0x09,0x83,0x2c,0x1a,0x1b,0x6e,0x5a,0xa0,0x52,0x3b,0xd6,0xb3,0x29,0xe3,0x2f,0x84,

0x53,0xd1,0x00,0xed,0x20,0xfc,0xb1,0x5b,0x6a,0xcb,0xbe,0x39,0x4a,0x4c,0x58,0xcf,

0xd0,0xef,0xaa,0xfb,0x43,0x4d,0x33,0x85,0x45,0xf9,0x02,0x7f,0x50,0x3c,0x9f,0xa8,

0x51,0xa3,0x40,0x8f,0x92,0x9d,0x38,0xf5,0xbc,0xb6,0xda,0x21,0x10,0xff,0xf3,0xd2,

0xcd,0x0c,0x13,0xec,0x5f,0x97,0x44,0x17,0xc4,0xa7,0x7e,0x3d,0x64,0x5d,0x19,0x73,

0x60,0x81,0x4f,0xdc,0x22,0x2a,0x90,0x88,0x46,0xee,0xb8,0x14,0xde,0x5e,0x0b,0xdb,

0xe0,0x32,0x3a,0x0a,0x49,0x06,0x24,0x5c,0xc2,0xd3,0xac,0x62,0x91,0x95,0xe4,0x79,

0xe7,0xc8,0x37,0x6d,0x8d,0xd5,0x4e,0xa9,0x6c,0x56,0xf4,0xea,0x65,0x7a,0xae,0x08,

0xba,0x78,0x25,0x2e,0x1c,0xa6,0xb4,0xc6,0xe8,0xdd,0x74,0x1f,0x4b,0xbd,0x8b,0x8a,

0x70,0x3e,0xb5,0x66,0x48,0x03,0xf6,0x0e,0x61,0x35,0x57,0xb9,0x86,0xc1,0x1d,0x9e,

0xe1,0xf8,0x98,0x11,0x69,0xd9,0x8e,0x94,0x9b,0x1e,0x87,0xe9,0xce,0x55,0x28,0xdf,

0x8c,0xa1,0x89,0x0d,0xbf,0xe6,0x42,0x68,0x41,0x99,0x2d,0x0f,0xb0,0x54,0xbb,0x16)

intermediate = sbox[tempPText[0][0] ^ tempKey[0][0]]

This will calculate the intermediate value for trace 0, looking only at subkey 0. This calculation can be repeated using list comprehension:

tempSbox = [sbox[tempPText[i][0] ^ tempKey[i][0]] for i in range(len(tempPText))]

Then, we need to get the Hamming weight of all of these intermediate values. We can do this using the same lookup table as the previous tutorial:

hw = [bin(x).count("1") for x in range(256)]

tempHW = [hw[s] for s in tempSbox]

Confirm that these look correct by printing them. (Would I ever steer you wrong?)

With these Hamming weights, we can look at every trace and decide which group it belongs in. Let's make a list of lists of traces:

tempTracesHW = [[] for _ in range(9)]

Then, we can loop through our list of traces and append each trace to the right category:

for i in range(len(tempTraces)):

HW = tempHW[i]

tempTracesHW[HW].append(tempTraces[i])

Now, tempTracesHW[y] is a list of all of the traces with an intermediate Hamming weight of y. As our last step, let's turn this into a list of NumPy arrays to make the math easier in the rest of the tutorial:

tempTracesHW = [np.array(tempTracesHW[HW]) for HW in range(9)]

One more check: make sure we have data in any one of these categories by printing

print len(tempTracesHW[8])

Points of Interest

After sorting the traces by their Hamming weights, we need to find an "average trace" for each weight. We can make an array to hold 9 of these averages:

tempMeans = np.zeros((9, len(tempTraces[0])))

Then, we can fill up each of these traces one-by-one. NumPy's average() function makes this easy by including an "axis" input. We can tell NumPy to find the average at each point in time and repeat this for all 9 weights:

for i in range(9):

tempMeans[i] = np.average(tempTracesHW[i], 0)

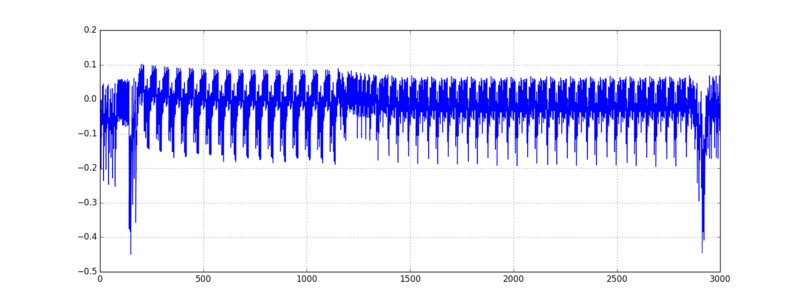

Once again, it's a good idea to plot one of these averages to make sure that the average traces look okay:

plt.plot(tempMeans[2]) plt.grid() plt.show()

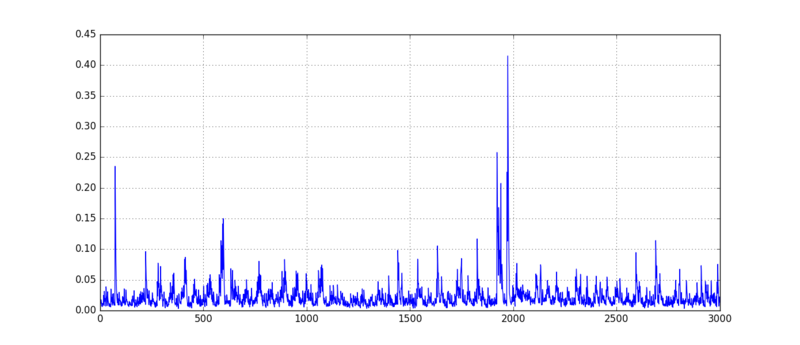

We can use these average traces to find points of interest using the sum of differences method. If this sounds unfamiliar, take a look at the theory page for a review of the math. The first step is to create a "trace" that stores these differences:

tempSumDiff = np.zeros(len(tempTraces[0]))

Then, we want to look at all of the pairs of traces, subtract them, and add them to the sum of differences. This is simple to do with 2 loops:

for i in range(9):

for j in range(i):

tempSumDiff += np.abs(tempMeans[i] - tempMeans[j])

This sum of differences will have peaks where the average traces showed a lot of variance. Make sure that there are a handful of high peaks that we can use as points of interest:

plt.plot(tempSumDiff) plt.grid() plt.show()

Now, the most interesting points of interest are the highest peaks in this sum of differences plot. However, we can't just sort the array and pick the top points. Remember (because you read the theory page, right? right?) that we need to make sure our points have some space between them. For instance, it would be a bad idea to pick both 1950 and 1951 as points of interest.

We can use the algorithm from the theory page to pick out some POIs:

- Make an empty list of POIs

- Find the biggest peak in the sum of differences trace and add it to the list of POIs

- Zero out some of the surrounding points

- Repeat until we have enough POIs

Try to code this on your own - it's a good exercise. If you get stuck, here's our implementation:

# Some settings that we can change

numPOIs = 5 # How many POIs do we want?

POIspacing = 5 # How far apart do the POIs have to be?

# Make an empty list of POIs

POIs = []

# Repeat until we have enough POIs

for i in range(numPOIs):

# Find the biggest peak and add it to the list of POIs

nextPOI = tempSumDiff.argmax()

POIs.append(nextPOI)

# Zero out some of the surrounding points

# Make sure we don't go out of bounds

poiMin = max(0, nextPOI - POIspacing)

poiMax = min(nextPOI + POIspacing, len(tempSumDiff))

for j in range(poiMin, poiMax):

tempSumDiff[j] = 0

# Make sure they look okay

print POIs

Covariance Matrices

With 5 (or numPOIs) POIs picked out, we can build our multivariate distributions at each point for each Hamming weight. We need to write down two matrices for each weight:

- A mean matrix (

1 x numPOIs) which stores the mean at each POI - A covariance matrix (

numPOIs x numPOIs) which stores the variances and covariances between each of the POIs

The mean matrix is easy to set up because we've already found the mean at every point. All we need to do is grab the right points:

meanMatrix = np.zeros((9, numPOIs))

for HW in range(9):

for i in range(numPOIs):

meanMatrix[HW][i] = tempMeans[HW][POIs[i]]

The covariance matrix is a bit more complex. We need a way to find the covariance between two 1D arrays. Helpfully, NumPy has the cov(a, b) function, which returns the matrix

np.cov(a, b) = [[cov(a, a), cov(a, b)],

[cov(b, a), cov(b, b)]]

We can use this to define our own covariance function:

def cov(x, y):

# Find the covariance between two 1D lists (x and y).

# Note that var(x) = cov(x, x)

return np.cov(x, y)[0][1]

As mentioned in the comments, this function can also calculate the variance of an array by passing the same array in for both x and y.

We'll use our function to build the covariance matrices:

covMatrix = np.zeros((9, numPOIs, numPOIs))

for HW in range(9):

for i in range(numPOIs):

for j in range(numPOIs):

x = tempTracesHW[HW][:,POIs[i]]

y = tempTracesHW[HW][:,POIs[j]]

covMatrix[HW,i,j] = cov(x, y)

Make sure these matrices look okay before continuing:

print meanMatrix print covMatrix[0]

Note that you may not have enough data to complete the covariance matrix - check out the Gotchas at the end of this tutorial if this step blew up on you.

Performing the Attack

Our template is ready, so we can use it to perform an attack now. We'll load our fixed-key traces and apply the template PDF to see how good each guess is, keeping a running total to check which subkey guesses are the best matches.

Loading the Traces

If you followed the instructions from the previous tutorial, you'll have a few dozen traces that use random plaintexts and a fixed key. We can load these in exactly the same way as the template traces:

atkTraces = np.load(r'C:\chipwhisperer\software\temp_attack\fixed_key_data\traces\2016.05.24-12.10.07_traces.npy') atkPText = np.load(r'C:\chipwhisperer\software\temp_attack\fixed_key_data\traces\2016.05.24-12.10.07_textin.npy') atkKey = np.load(r'C:\chipwhisperer\software\temp_attack\fixed_key_data\traces\2016.05.24-12.10.07_knownkey.npy')

In particular, let's check the key to make sure we know what our goal is:

print atkKey

With the default key in ChipWhisperer Capture, this prints

[ 43 126 21 22 40 174 210 166 171 247 21 136 9 207 79 60]

We're only attacking the first subkey, so let's see if we can get 43 to come up as the best guess.

Using the Template

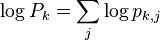

The very last step is to apply our template to these traces. We want to keep a running total of  , so we'll make space for our 256 guesses:

, so we'll make space for our 256 guesses:

P_k = np.zeros(256)

Then, we want to do the following for every attack trace:

- Grab the samples from the points of interest and store them in a list

- For all 256 of the subkey guesses...

- Figure out which Hamming weight we need, according to our known plaintext and guessed subkey

- Build a

multivariate_normalobject using the relevant mean and covariance matrices - Calculate the log of the PDF (

) and add it to the running total

) and add it to the running total

- List the best guesses we've seen so far

Our implementation is:

for j in range(len(atkTraces)):

# Grab key points and put them in a matrix

a = [atkTraces[j][POIs[i]] for i in range(len(POIs))]

# Test each key

for k in range(256):

# Find HW coming out of sbox

HW = hw[sbox[atkPText[j][0] ^ k]]

# Find p_{k,j}

rv = multivariate_normal(meanMatrix[HW], covMatrix[HW])

p_kj = rv.pdf(a)

# Add it to running total

P_k[k] += np.log(p_kj)

# Print our top 5 results so far

# Best match on the right

print P_k.argsort()[-5:]

The output that appears is:

[219 145 181 134 127] [ 37 43 76 123 235] [32 44 45 77 43] [199 45 44 77 43] [139 37 42 77 43] [45 77 37 42 43] [235 37 45 42 43] [ 37 77 139 235 43]

This means:

- After 1 trace,

43wasn't even in the top 5 guesses. This is fine - there are probably a lot of key candidates tied for first place. - After 2 traces,

43was the 4th best guess - pretty good... - After 3+ traces,

43was the best candidate for the subkey.

so we successfully attacked the first subkey in 3 traces! This is a bit lucky - most of the subkeys tend to take a bit more data. Don't be surprised if your attack takes closer to a dozen trials.

Gotchas

One problem with template attacks is that they require a large amount of data to make good templates. Remember that every output of the AES substitution box is unique, so there is only one output with a Hamming weight of 0 and only one with a weight of 8. This means that, when using random inputs, there is only a 1/256 chance of a trace using a Hamming weight of 0 or 8.

When only recording 1000 examples, it is completely possible to never see one of the weights, making it impossible to find the mean and variance. In fact, seeing a weight once is not enough - in order to calculate the variance, we need at least 2 traces, and this is hardly enough to build a good distribution.

Some template attacks involve building a separate distribution for every possible subkey. This makes the problem even worse - now, we have a 1/256 chance of finding every key, so it's quite probable to have insufficient data. The only solution is to record more traces. Practical template attacks may require tens of thousands of traces to get enough information.

If you ran into numerical problems while working through this tutorial, try recording another bigger data set. Instead of capturing 1000 template traces, try 5000 (on your coffee break), 10000 (on your lunch break), or 100000 (overnight). You'll probably find that the extra data makes the statistics work out better.