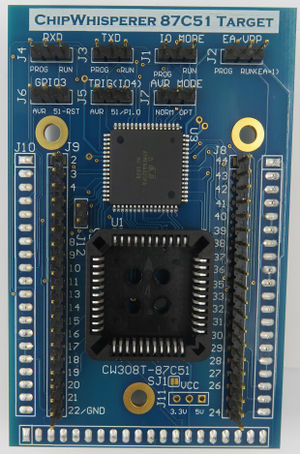

CW308T-87C51

| CW308T-87C51 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Target Device | 8xC51 |

| Target Architecture | 8-bit 8051 |

| Hardware Crypto | Possible |

| Design Files | OSH Park PCBs |

The 87C51 target is designed for a line of 8051 processors made by Intel in PLCC44 package, although other manufactures make equivalent devices as well (notably NXP as well). This target board allows for two types of side channel attacks:

- Regular power analysis or glitching on the 87C51 firmware (ex: attacking an AES key while the 87C51 performs AES encryption)

- Attacks on the verification process in order to bypass the device's encryption table or security fuses

This page describes the setup of the 87C51 target and shows how it can be used to perform these two types of attacks.

Hardware Details

Programming Microcontroller

The target board contains an ATMega165PA/ATMega325PA (referred to as the 'AVR' hereafter), which can be used for performing program verification. It is also used to generate trigger points for attacks such as encryption table read-out & inserting glitches into the program read logic. The programming interface contains the following limitations:

- No programming is possible as there is no VPP generation.

- Address lines A0 - A13 are mapped to the AVR. The upper two lines are shared with LED1/LED2 outputs. (A14 and A15 aren't needed because the 87C51 model that's used only has 16 KB = 2^14 bytes of memory.)

Target Microcontroller

The default target device is an Intel EE87C51RB1 (16K EPROM, 512 RAM). Useful references:

NOTE: The Intel datasheet is fairly short (20 pages) and does not include full details of the programming. This can be found in the NXP datasheet.

There are 2 20-pin headers on the top side of the board connected to the pins of the 87C51. If you're keeping track, the remaining 4 pins are labelled NC - they aren't used internally, so all of the functional pins are broken out to these headers. These headers make it easier to connect an oscilloscope or logic analyzer to the target.

Jumpers

A number of jumpers are present on the target board. They are mostly used to select different features and options on the target board. First, there are 7 jumpers that connect to the IO lines of the two microcontrollers

- IO MODE (J1): Selects if the AVR is enabled or not. When the board is powered on, if this is set to "RUN", the AVR will enter sleep mode until the power is cut. If it is set to "PROG", the AVR will continue executing its program.

- EA/VPP (J2): Selects the 8051's EA pin connection. In "PROG" mode, the AVR has control of this pin; in "RUN" mode, it is always set to 1. This is necessary to allow the 8051 to execute code from internal EPROM memory.

- TXD (J3): Connects the Target IO2 line (Serial TXD) to one of the chips. In "PROG" mode, this is connected to AVR PE1. In "RUN" mode, it is connected to 8051 P3.1.

- RXD (J4): Connects the Target IO1 line (Serial RXD) to one of the chips. In "PROG" mode, this is connected to AVR PE0. In "RUN" mode, it is connected to 8051 P3.0.

- GPIO4 (J5): Connects the Target IO4 line to AVR PE3 ("AVR" mode) or 8051 P1.0 ("51/P1.0" mode). This line is intended to be used as a trigger, so firmware on the 8051 and AVR can cause a trigger by toggling these wires.

- GPIO3 (J6): Connects the Target IO3 line to AVR PE5 ("AVR" mode) or 8051 RESET ("51-RST" mode). In the former, the AVR has control over the 8051's reset line. In the latter, the 8051 uses an active-high reset, so the device runs when GPIO3 is set low.

- AVR MODE (J7): Connects to AVR PE4. This is normally pulled up to VCC. With a jumper connected in "OPT" mode, this is set low.

Then, there are two jumpers that control the power and clock signals:

- VCC (J11): Connects to the board's VCC rails. This can be connected to the baseboard's 5V rail or to one of the 3.3V regulator outputs. Be cautious with this - in particular, the ChipWhisperer Lite does NOT have 5V tolerant IO lines!

- J12: When J12 is not connected, the AVR runs on its own 7.37 MHz crystal. With J12 connected, the AVR's clock line is connected to CLKIN signal, which is also the 8051's clock line. Connecting the clock signals is useful for ensuring that the devices are synchronized, but it also causes any glitched clock signals to be routed to AVR.

Finally, the baseboard's "Target-Defined Programming" header (J15) is connected to some of the 8051 pins. P3.3, P3.4, and P3.5 are connected to H2, H4, and H6. Normally, these pins are all pulled down to ground (logic 0). When a jumper is mounted to H1-H2, H3-H4, or H5-H6, these pins are instead connected to VCC (logic 1).

AVR Firmware

The AVR on the target board has its own firmware to control the 87C51 code verification process. This firmware is one Atmel Studio project in the Git repository. The compiled hex file can be programmed onto the AVR using the AVR Programmer in the capture software.

If you have a target board that's never been programmed before, the AVR fuses will need to be programmed from their default values. A fuse calculator is helpful here. The fuses should be written to:

- Low fuse:

0xED - High fuse:

0x99 - Ext fuse:

0xFF

To program these, the AVR programmer will have to use Slow Clock Mode. Once these fuses are set, slow clock mode can be disabled again.

87C51 Firmware

Developing Firmware for the 87C51

There are a number of tools that can be used to develop firmware for the 87C51 processor. The best 8051-specific software can be pretty expensive, but it is possible to get by with free software:

Compiler: The SDCC (Small Device C Compiler) is a compiler that is made for devices with limited amounts of memory. It can be used to compile code specifically for a number of targets, including the 8051 line of processors. A few of the useful flags are:

-

-mmcs51: Compile code specifically for an MCS51 target -

--iram-size [size]: Specify that the device has[size]bytes of internal RAM -

--xram-size [size]: Same as above, but for external RAM -

--code-size [size]: Same as above, but for code memory (EPROM) -

--out-fmt-ihx: Produce an Intel HEX file as the output of the linking stage -

--stack-auto: Put all automatic variables on the stack, rather than storing a specific location in RAM for them. This can be a huge RAM saver!

Note that SDCC has not completely implemented the ISO C99/C11 standards. One very noticeable change is that SDCC does not allow variables declarations to be intermingled with code. That is, the following will not compile:

void func()

{

int x = 1; // OK

x += 2; // OK

int y = x; // syntax error: token -> 'int'

}

Simulator: The 87C51 is one-time programmable, so it is extremely helpful to have a simulator to test firmware before burning it onto a physical processor. There are very few free simulators for the 8051 core. One free sim is EdSim51. This program can load a hex file and run the code one step at a time. There are a few big issues:

- The simulator has no way of translating your compiled binary file back into C. This means that the debugging process is a bit blind - moving through the program one line at a time isn't particularly helpful because one line of C will typically be many lines of assembly. It's still possible to debug code by printing variables, but this leaves something to be desired.

- EdSim51 is designed for an 8051 core with 128 B of RAM. This means that you cannot simulate any programs that use more than 128 B of RAM. However, this is enough space for a lot of tasks - our full piece of firmware does AES over SimpleSerial in this much space!

Programmer: To write a program into the code EPROM, an EPROM programmer is needed. We used a MiniPro TL866 programmer along with their free software. However, any programmer compatible with the 87C51 should be fine.

Example Firmware

We've written a couple of firmware examples and put them together into one big 87C51 project. Combining multiple pieces of code together means that we can use one chip for all of the side channel attacks - we don't need separate processors to work on different pieces of firmware. This project has six different parts:

-

print: prints "Testing 1\nTesting 2\nTesting 3...". Easy to confirm that the processor is running correctly. -

passcheck: waits for the user to enter a password and checks whether it is correct. The correct password is "Tr0ub4dor&3\r". -

glitchloop: calculates 200 * 200 using a very long and tedious loop. Inserting a successful glitch will corrupt this result. -

xor: implements the SimpleSerial protocol with 128 bit key and plaintexts. The response is the XOR of the plaintext and key. -

aes: implements SimpleSerial with AES-128 encryption (128 bit key and plaintext) -

tea: implements SimpleSerial with TEA encryption (256 bit key and 128 bit plaintext)

When the 87C51 is powered on, it reads the state of the Target-Defined Programming header J15 to decide which mode to run in. In the following table, a Y means that the jumper is mounted, and an N means that no jumper is mounted:

| H5-H6 | H3-H4 | H1-H2 | Mode |

| N | N | N | |

| N | N | Y | Password check |

| N | Y | N | Glitch loop |

| N | Y | Y | XOR |

| Y | N | N | AES |

| Y | N | Y | TEA |

| Y | Y | N | — |

| Y | Y | Y | — |

Code Verification

Verification Process

The process to read back code from the 87C51's EPROM memory is described in the NXP datasheet (in the EPROM Characteristics section). However, there's a lot of info in this section about writing to the EPROM memory, which we can't do on the target board. The bare minimum to verify code bytes is repeated here:

1. Set the following levels on these pins:

| Pin | Level |

| RST | 1 |

| P3.6 | 1 |

| P3.7 | 1 |

| EA/VPP | 1 |

| ALE/PROG | 1 |

| PSEN | 0 |

| P2.6 | 0 |

| P2.7 | 1 |

2. Write the 16 bit address to the following pins:

| Pin | Address |

| P1.0-P1.7 | A0-A7 |

| P2.0-P2.5 | A8-A13 |

| P3.4 | A14 |

| P3.5 | A15 |

Note that the 87C51 that we've used for this project only has 16 KB of memory, so addresses over 0x3FFF are meaningless (ie: A14 and A15 have no purpose).

3. Write P2.7 to 0 to begin the read. Wait at least 48 clock cycles.

4. Read the 8 bits of data from P0.0-P0.7. These pins use open drain outputs, so pull-up resistors are needed - the AVR's internal pullups are good enough for this.

5. Write P2.7 to 1 to stop reading the device.

Security

There are two security features built into the 87C51 to stop end-users from reading the firmware out of EPROM. Companies might use these features as an anti-piracy measure: if they can keep their competitors from reading their source code, then they can avoid giving away any of their trade secrets. Both of these security features can be enabled using the Minipro programmer.

First, the 87C51 has a 64 byte encryption table stored in EPROM. By default, this table contains 64 0xFF bytes. When the chip is being programmed, the table can be loaded with secret values. Then, when a byte of the code is read from the code memory, it is XNORed with a corresponding byte from the encryption table. In pseudocode, this is

displayed_byte = ~(data[address] ^ enc_table[address % 64]);

Notice that the default encryption table has no effect on the data - there is no encryption until the table has been written with some values.

Second, the 87C51 has three lock bits that can be enabled. Lock bit 2 cannot be enabled until lock 1 is, and lock 3 cannot be enabled until lock 2 is. The three locks have the following functions:

- EPROM can no longer be programmed. Also, some restrictions are placed on programs that use external memory.

- Verification is disabled. The device will read

0xFFfor every address. - Programs cannot be executed from external memory.

The most critical of these locks is the second: it stops all verification.

Gotchas

This section describes a few quirks/caveats that we found with the 87C51 and its target board.

The 87C51 does some crazy things with the clock signal. First, the external clock is fed into a divide by 2 counter to guarantee a 50% duty cycle. Second, every instruction that the 8051 core executes takes a multiple of 6 clock cycles. In other words, one "machine cycle" on the chip is 6 internal cycles, which is 12 oscillator cycles.

When performing side channel attacks on the verify process, the relative phase of the "machine clock" is important: the power consumption changes significantly if we load the address on oscillator cycle 1, 2, 3, ..., or 12. (The changes are more severe than a simple shift in time.) To avoid these phase shifts, we tried to synchronize the AVR's verify methods with the 8051's machine clock. We found that the 8051 has an output (ALE/PROG) that is used for external timing - it is emitted at 1/6 of the oscillator frequency. By syncing to this signal, we narrowed down the phase shift from 12 possible shifts to 2. However, we could not find a way to remove this 1/2 chance. If you are capturing multiple sets of traces, please look to see that the main features of the traces don't move between captures!

The 87C51 has a synchronous reset input (?!) - a reset requires 12 oscillator cycles to take effect, and the machine clock's phase does not change during a reset! This means that the only way to change the machine clock's phase is to power cycle the 87C51. (The "Read Signature" button in the AVR Programmer does this. Pulling out the processor and re-mounting it does too.)